I can’t draw. In fact, I’m so bad at drawing that anytime I played the game Pictionary, none of my teammates could ever guess what I was attempting to represent.

It was a bit embarrassing, but I was fully aware of my artistic limitations. Anything beyond basic stick figures was completely out of my realm.

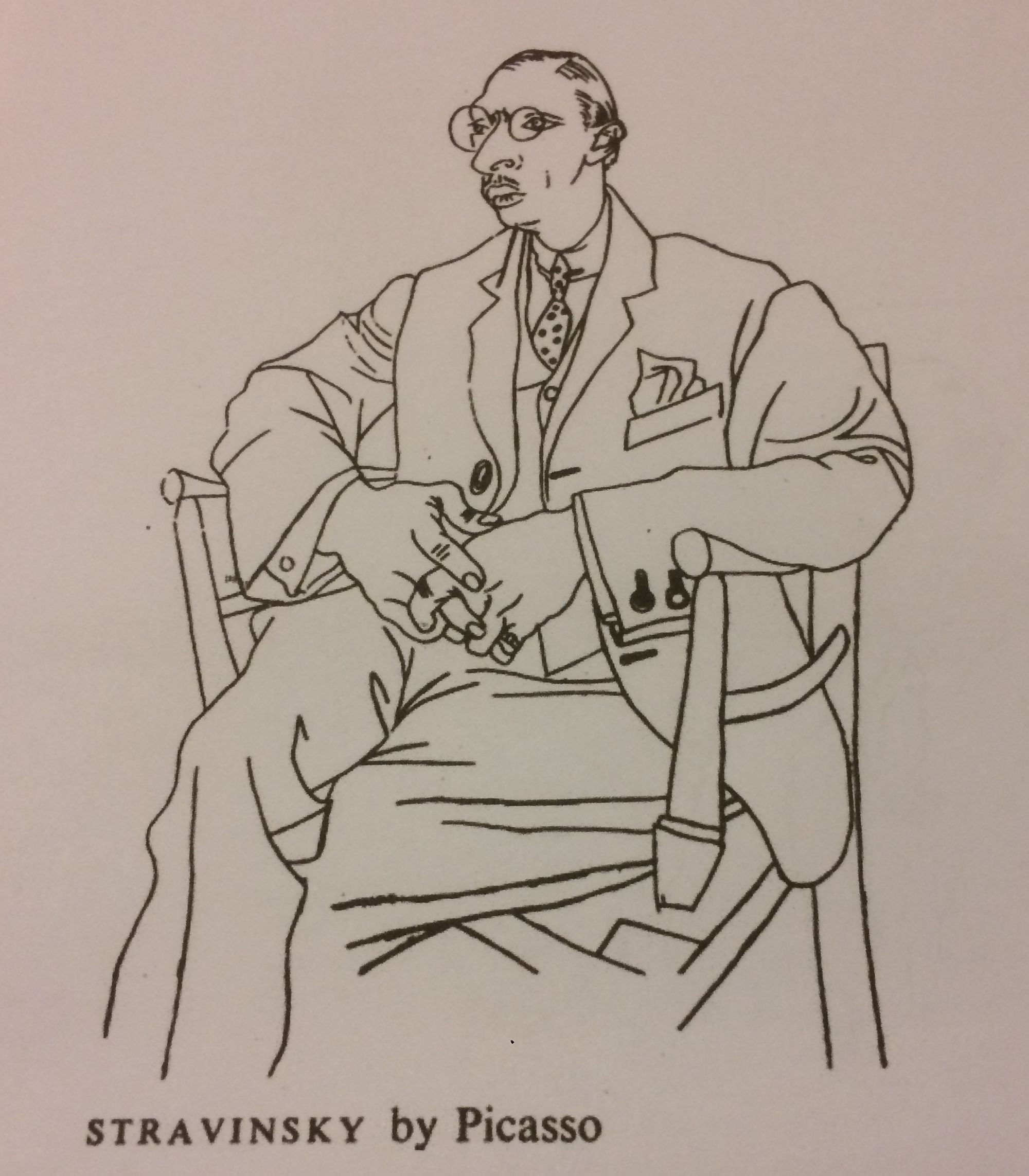

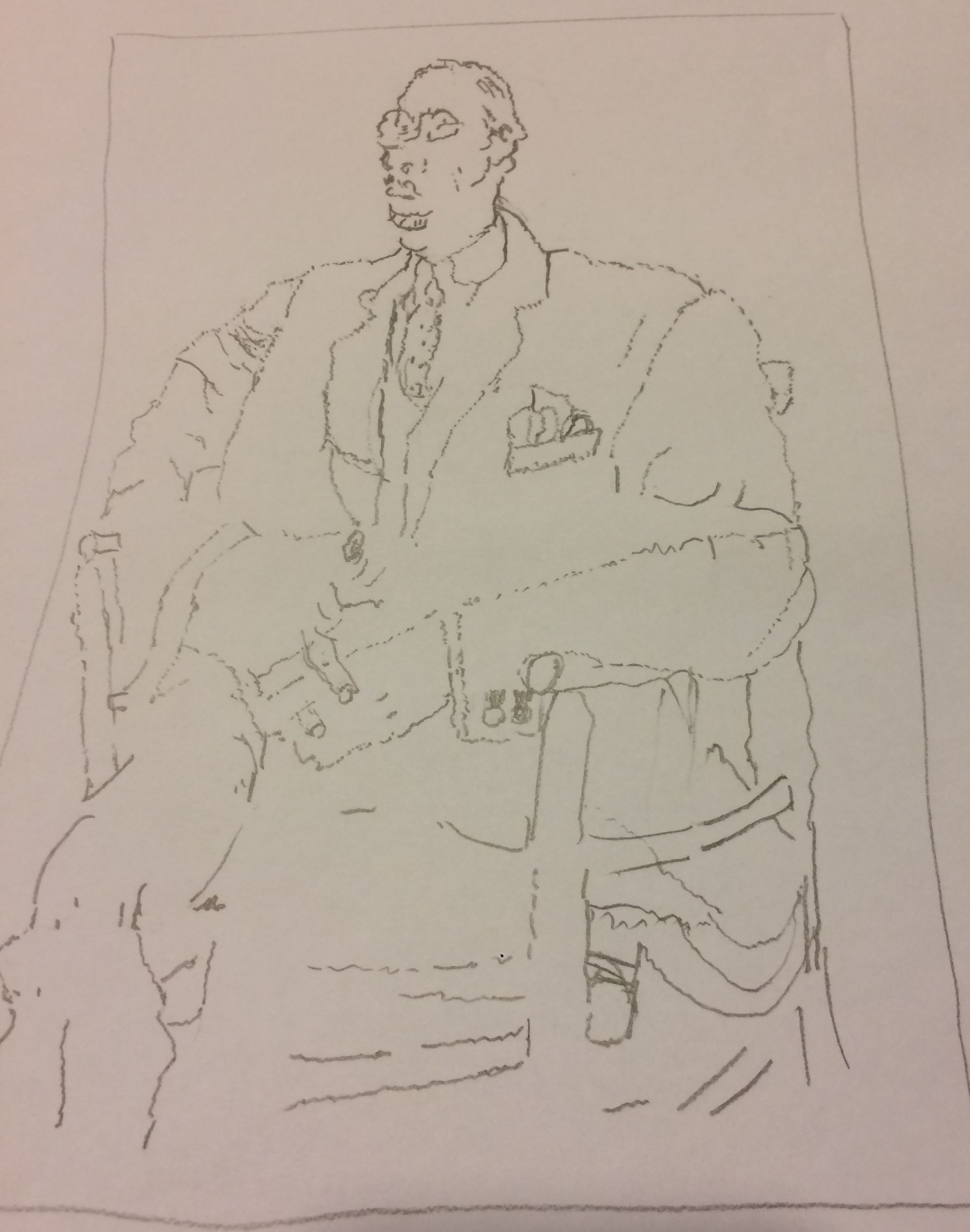

Yet with zero training and no practice, I just drew a fairly close representation of Pablo Picasso’s sketch of Igor Stravinsky.

When I finished my drawing, I was totally shocked by what I saw – so much so that it gave me goosebumps.

How did I perform such a feat?

By getting into the right hemisphere of my mind and reproducing Picasso’s sketch upside down.

Yes, upside down.

In the brilliant insight of artist Dr. Betty Edwards, nearly anyone can learn to draw by getting out of their left hemisphere.

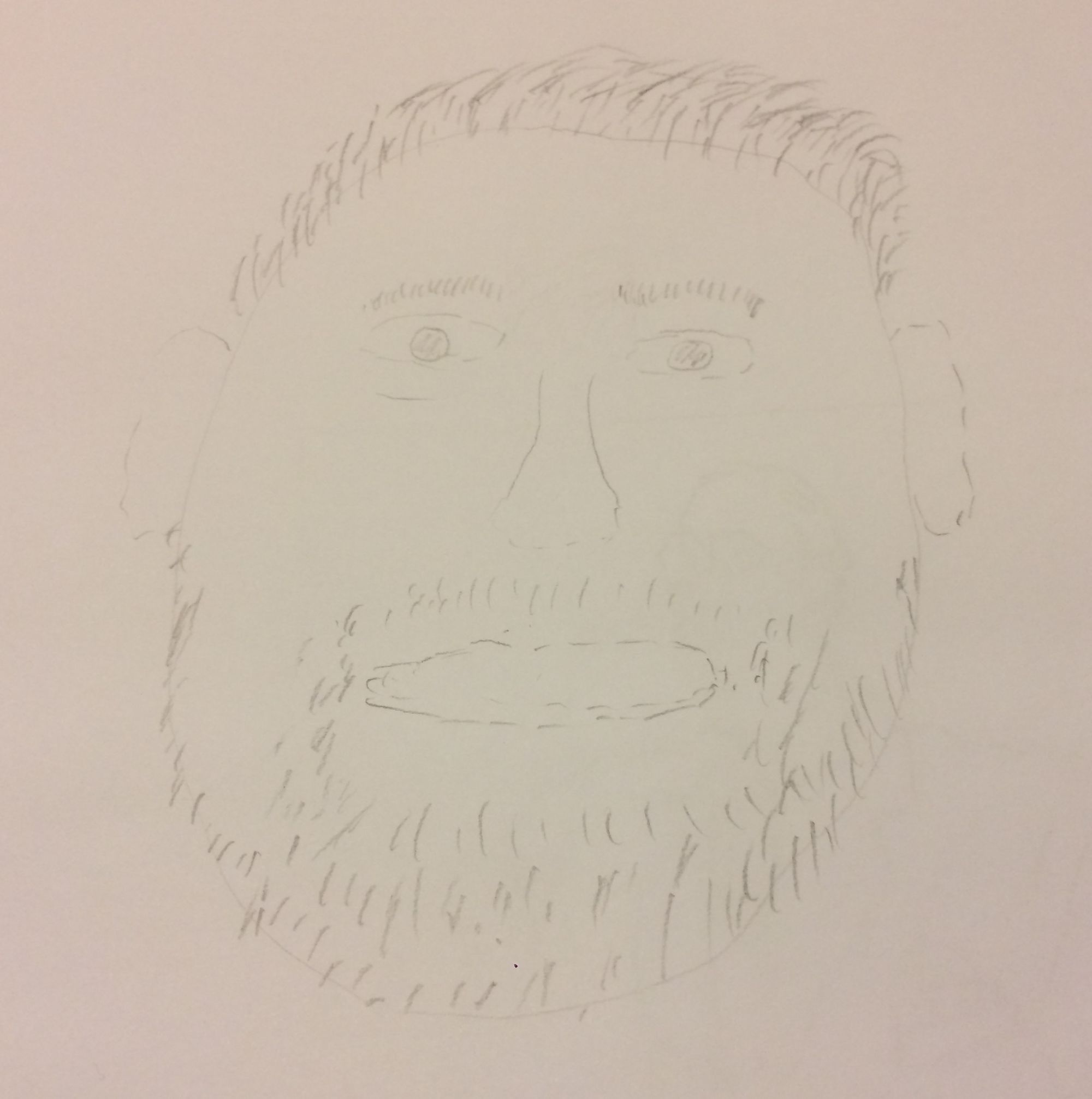

She instructs students to perform two exercises: the first is to draw a self-portrait. That’s it – you’re given a blank sheet of paper and told to draw yourself.

My self-portrait was, as predicted, terrible. Not a single person who looked at that picture – even people who know me best – would say it even comes close to representing me.

The reason this looks so bad, it turns out, is that I was drawing from my left hemisphere.

This is the realm of logic, assumptions, generalizations, simplifications, and judgement. In this mind, we use words to name things and we are goal-oriented to accomplish the task. “The nose goes here. Now I need to add the eyes, and then I’ll add the eyebrows right here. Let’s add some squiggly lines here for hair.”

In this state, we don’t see subtlety and complexity and dimensionality. So we classify objects like noses and hair as fairly general. There was very little nuance in my drawing – just very basic shapes. When I stepped back and looked at my self-portrait, I was right back in the Pictionary game conjuring up the familiar jeers: “That’s supposed to be a horse? Really?!”

Needless to say, I wasn’t particularly eager to continue on to Dr. Edward’s second exercise, but by this point, I was committed to do so.

And this is where her superb insight comes into play.

“Draw this image you see here.” And the image she wants us to draw is upside down and pixelated. It’s some sort of person, but hard to tell with any clarity unless you flip the image the right way. But that’s part of the exercise – we aren’t allowed to flip the image correctly.

Instead, we are asked to look at this upside down image, starting from the bottom, and simply draw on our canvas what we see – pixel for pixel.

And here’s where magic occurs. Because I can’t tell what anything is, my left hemisphere (which is the seat of the ego) can’t name it. All it sees is a bunch of lines and squiggles, so it gets bored and gives up the task.

Enter the right hemisphere that happily draws what it sees. There is no judgment and not even a sense of time passing. We get into a state of meditative “flow” reproducing the lines and pixels from the drawing.

At one point, I realized I was drawing a finger. And then all of a sudden I was back in my ego. “I know what a finger should look like. And the nail should go here …”. The peace that I had felt dissolved, and now I was judging how bad my drawing of the upside-down finger looked. But once I covered up the rest of the hand on the original, it no longer looked like a finger and I easily slipped back into my right brain and continued with the process.

As long as I couldn’t discern what I was drawing – just lines and pixels – I was able to easily continue in that peaceful state until I reached the top of the drawing (having started at the bottom). Once I finished, however, my ego jumped right back in and said, “This is going to look awful.” And I truly believed that.

The first step was flipping the original image. “OK, that’s Picasso’s sketch of Igor Stravinsky. There’s no way my drawing is going to look like this.”

I tentatively flipped my drawing, fearing the Pictionary ridicule about to rear its ugly head.

“OMG, my drawing is pretty darn close to Picasso’s! How did that happen?!”

It’s not that I suddenly became an artist. But as Dr. Edwards says, “You already know how to draw. But old habits of seeing interfere with that ability and block it.”

Most of us spend the majority of our time in the ego of our left hemisphere. That’s where judgement, analysis, logic, and goal orientation reside. But when we can learn to get into our right mind, we are capable of far greater accomplishments.

In additional to experiencing a Zen-like state of flow, we’re able to participate on tasks without judgement. Imagine being able to work and interact with others without ever getting angry, frustrated, jealous, or disappointed?

Imagine being able to have a stronger sense of intuition, empathy, creativity, and big-picture thinking. That’s what happens when we step out of the ego mind and into our right mind.

Albert Einstein, one of the greatest thinkers of the 20th century, is most noted for his famous relativity equation unifying energy and mass (energy = mass times the speed of light squared, or E = mc^2). Einstein worked for years struggling with the equations, truly convinced that his quest was hopeless. Clearly he was in his left hemisphere.

One night, he went to bed deeply depressed. But he was willing to step out of his ego mind. And what happened next is the stuff of legend. The theory of relativity came to him suddenly. As he said, “a huge map of the universe outlined itself in one clear vision.”

The challenge with our ego is that it believes it knows everything it needs to know. It rushes to premature conclusions. And it loves (and needs) to be right. It’s mantra could be summed up as “me vs. the world.”

Our right minds, on the other hand, not only see the big picture, but see the shared purpose that unites every one of us.

As Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor shares in her Stroke of Insight TED talk (she suffered a stroke and temporarily lost all connectivity to her ego), “In the absence of my left hemisphere’s analytical judgment, I was completely entranced by the feelings of tranquility. Freed from all perception of boundaries, my right mind proclaims, ‘I am a part of it all.’”

So, if we want to practice being a better teammate, a more inspiring and visionary leader, enhancing our intuitive skills, and feeling a greater sense of peace – all we need to do is spend some time getting out of our ego. And one of the best ways to do that is by quieting our judgmental ego by becoming more of an observer.

How to do that?

As soon as we catch ourselves reacting to a situation (and we know we’re reacting if we’re having any emotions such as anger, frustration, an urge to reply, etc.), take a deep breath (with an especially long exhale) and simply name the emotion we’re feeling. “Oh, that’s anger.”

By witnessing what’s going on, we temporarily step out of the drama of the situation. And the more we practice, the faster the negative emotions pass by without keeping us so tightly in their grip. We become less judgmental of others – and ourselves – and we open ourselves to the amazing feeling of right minded living.

Besides leading a much more rewarding life, we might even become a great artist.